The Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) is all about nature and how we must all take progressive actions to reverse the global loss of biodiversity. COP15 has been somewhat overshadowed by the higher-profile Climate COP – COP27 – which recently took place in Egypt, but due to the climate emergency being inextricably linked to the nature crisis, is equally important. Four years in the making, delayed by the Covid 19 pandemic, COP 15 is a once-in-a-decade chance to turn the tide for nature. For our ocean, this has never been more needed.

At the United Nations Ocean Conference in June 2022, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres declared that we are facing an “ocean emergency”, an inevitable result of the intertwined climate and nature crises given that the ocean has already absorbed so much excess carbon dioxide and heat arising from our burning of fossil fuels. In Scotland, breeding seabird numbers had declined by almost 50% since the 1980s[1], even before the devastating 2022 outbreak of Avian Influenza (‘bird flu’). Scotland’s Marine Assessment 2020[2] also paints a stark picture of poor seabed health, with living seabed habitats particularly diminished and vulnerable,and iconic species such as Atlantic salmon in decline. It emphasises bottom-contacting and pelagic fishing as the most “geographically widespread, direct pressures” and climate change as the “most critical factor” affecting Scotland’s marine environment.

At COP 15, world leaders will finally agree on new, binding targets for the protection and recovery of biodiversity under a post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). The draft GBF is currently proposing a target that would bind signatory countries to at least 30% of their land and sea being covered by systems of protected areas. It sets the global minimum standard for protection of ecosystems. Importantly, the Framework identifies the main drivers of biodiversity loss that must be addressed, with global food production the top concern. For our seas in Scotland, this means industrial pressures such as bottom-contact mobile fishing gear and aquaculture need to be transformed to support the recovery, rather than drive the decline, of nature.

Networks of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are one of the key conservation tools in a country’s toolbox to protect and recover nature. They are areas of sea with greater levels of protection than surrounding areas, often identified for particular species, habitats or ecosystems of conservation importance where activities that pose the greatest risk to these features are restricted. This latter point is key, as an MPA is only as good as the management measures put in place within it. Currently, there are 232 MPAs in Scotland’s seas designated for nature conservation, but only a small percentage of these have legally binding restrictions on bottom-contact fishing activities, and many other marine industries continue to operate within the sites. These measures will currently, at best, protect small areas of marine biodiversity that are left but are unlikely to enable the large-scale ecosystem recovery that is needed, and therefore do not yet fulfil the commitment to truly protect at least 30% of our seas.

In the Bute House Agreement – the Scottish Government and Scottish Green Party’s co-operation agreement and shared policy programme – there is a commitment to complete the fisheries management measures for the remainder of the existing MPA network by 2024. Though delayed, this is welcome, and in our view must deliver a “whole-site approach” to protecting the existing MPAs, where bottom-contact fishing gear is excluded from sites designated to protect seabed habitats.

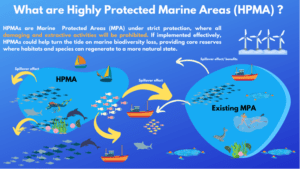

The agreement also includes an ambitious new commitment to designate at least 10% of Scotland’s seas as Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs) by 2026. These HPMAs are MPAs under even stricter protection, where all damaging and extractive activities will be prohibited[3]. In conjunction with bolstering the protection of the existing MPA network, if implemented effectively, HPMAs could help turn the tide on marine biodiversity loss, providing core reserves where habitats and species can regenerate to a more natural state.

Why do we need HPMAs in addition to the existing MPAs in Scottish seas? Imagine HPMAs as a fully protected core of the MPA network, providing sanctuaries for marine life from all extractive or damaging activity. These new areas can be targeted to degraded or altered areas where ecosystem recovery is most needed, complimenting the wider MPA network. Sites in the existing network were identified to protect, and in some places recover, the best of the biodiversity remaining after centuries of human impact and decline, and include more targeted protections for specific species and habitats but still allow some types of fishing, aquaculture and other activities such as cable-laying and wind-farms.

In combination, an ecologically coherent network of HPMAs and MPAs can help support the recovery of nature that has declined, the protection of nature that remains in good condition and ensure that our seas continue to provide benefits to society (ecosystem services) such as food, energy and recreation. .

It is important to emphasise that people will be able to access HPMAs for recreation and enjoyment. Non-extractive, non-damaging activities will be possible at levels clearly defined to ensure they do not impact the site. As stated in the Benyon Review, HPMAs can provide multiple social and economic benefits such as marine tourism and recreational activities, and opportunities for scientific research and education. They can have a positive impact on human health, and enhance the aesthetic, cultural and religious significance of the area.

With only eight years left to turn around the decline of nature on land and at sea, COP15 has to deliver bold global commitments for ocean recovery. In Scotland, it is vital that the existing MPA network is swiftly protected from industrial pressures such as bottom-contact fishing gear, and thereafter that at least 10% of our large patch of the northeast Atlantic is protected from all forms of damaging activity and all types of fishing within new HPMAs.

Esther Brooker and Fanny Royanez, Marine Policy and Engagement Officers at LINK

This blog is part of the LINK Thinks COP15 series. Click here to read the series of blogs by LINK staff, members and Honorary Fellows who will be highlighting the importance of targeted action in protecting and restoring our precious nature over the course of the conference.

[1] https://www.nature.scot/seabird-numbers-decline-almost-50

[2] https://marine.gov.scot/sma/

[3] Equivalent to International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) protected area category 1A: ‘Strict nature reserve: Strictly protected for biodiversity and also possibly geological/ geomorphological features, where human visitation, use and impacts are controlled and limited to ensure protection of the conservation values’

Image: Calum McLennan