It’s the holy grail of marine conservation, or at least it is to many skippers, fisheries managers and governments. The win-win-win: whereby improving the ecological health of our seas leads to real in-the-pocket benefits for the fishing sector, with higher value landings (based on a combination of increased biological productivity and high-value catch) making a positive contribution to the national balance sheet. It’s no surprise that it is the focus for extensive scientific research across the world.

It’s the holy grail of marine conservation, or at least it is to many skippers, fisheries managers and governments. The win-win-win: whereby improving the ecological health of our seas leads to real in-the-pocket benefits for the fishing sector, with higher value landings (based on a combination of increased biological productivity and high-value catch) making a positive contribution to the national balance sheet. It’s no surprise that it is the focus for extensive scientific research across the world.

There is increasing evidence that MPAs offer significant long-term secondary economic benefits flowing from the environmental benefits of sustainably managing human activity within a marine area. However, this can often mean reducing some types of commercial fishing in the first place, which sometimes gives MPAs a bad name. Therefore establishing an MPA is not something that can be done lightly, as there may be short-term social and economic impacts as a result of the management measures imposed. Managers must be aware of these impacts, particularly where the fishery provides an important source of income for local communities. So perhaps the question should be: do the societal benefits of MPAs outweigh the potential societal impacts?

Over the next couple of months, we are going to highlight the issues involved more closely and review some case studies of MPAs (that allow some extractive activity) or Marine Reserves (MRs – a more highly protected type of MPA where no extractive activity is allowed) that have been established for a number of years and are now starting to show changes to the local marine ecosystem as a result.

The theory

MPAs vary greatly around the world and their purpose, objectives and management measures will depend on local or regional issues. Here in Scotland, our nature conservation MPAs are multi-use, meaning that they are not completely no-go or no-take areas, but will be managed so that activities are permitted in a way that will not compromise the reason for establishing them, which is to achieve the conservation objectives of the site.

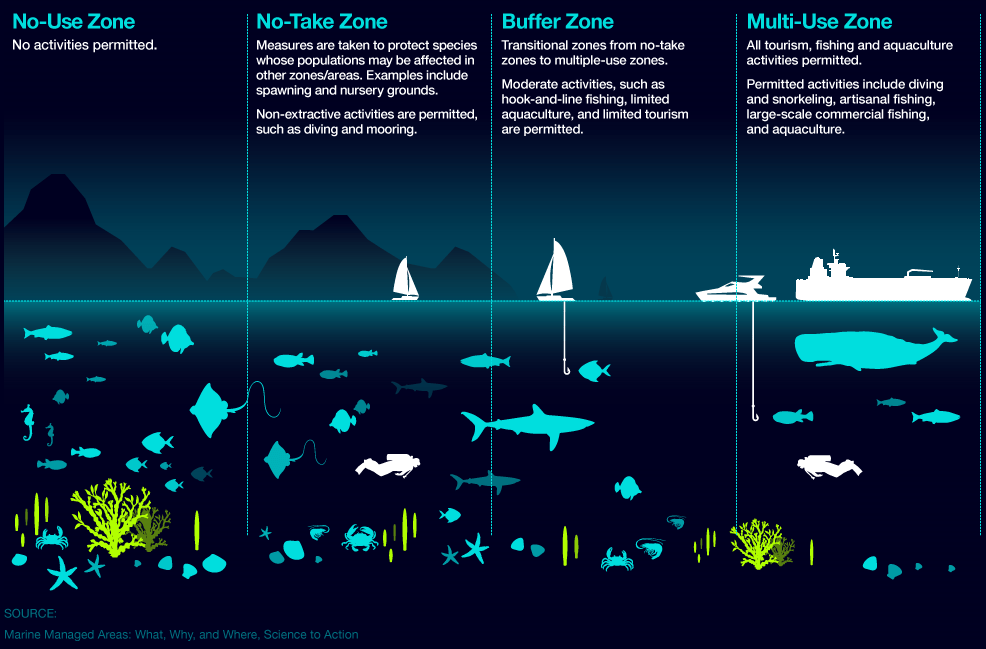

The infographic below illustrates the different types of zones that may be designated within an MPA to manage the different activities and also shows what the likely state of the biodiversity will be in the different zones. The health of the sea in the different zones is thought to be influenced directly by the types of activities in the area – simply put, with greater levels of extractive activities (e.g. fishing, aggregate extraction and deep sea mining), the ecosystem will be less diverse.

Environmental change occurs much slower in the sea than on land, so in order to understand the nature of any changes that may result from establishing an MPA at a species population level, scientists need to collect data over a long period of time – ideally more than 20 years, although initial changes can be observed in less time. Unfortunately there are not many MPAs that have been established for more than 20 years, so evidence is still only just emerging. It’s clear that it’s not only about direct impacts on species (for example, fishing a particular type of fish stock), but it’s about the wider resilience of the ecosystem upon which a species depends. In short, there’s no point applying a regulation prohibiting fishing for one species if its habitat can still be impacted by human activities – proper protection is about safeguarding the whole ecosystem and maintaining it as a complex system to support life in our seas.

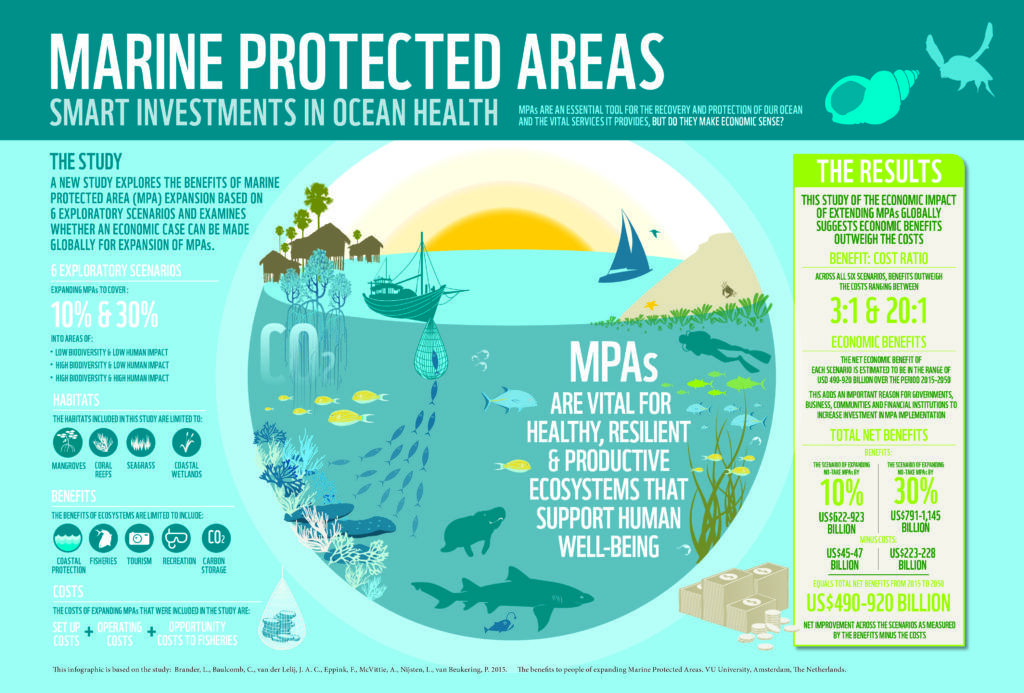

This image illustrates the findings of research commissioned by WWF International on the benefits of increasing the number of MPAs that protect critical habitats across the world .

This study describes scenarios based on the best available evidence (rather than empirical field data), and paints a very positive picture of MPAs that are managed to protect and recover important habitats. It suggests that the benefits of increasing marine protection would significantly outweigh the costs, offering a strong economic argument for MPAs supporting human life as well marine life.

Sounds very positive doesn’t it? But it’s difficult to translate this global scenario to what this means for us here in Scotland. So let’s take a closer look at some case studies that might give us an idea of what we can expect our own MPAs to deliver – or start delivering – in a few years’ time.