June 13th, 2023 by morag

By LINK’s Chief Officer Deborah Long – first published in The National, 22nd May.

Scotland is a land of contrast. Contrasts in our landscapes, in our geography and weather patterns, our language, culture and our traditions.

Scotland has world-leading access legislation ensuring that everyone, no matter who they are, can access and enjoy Scotland’s outdoors, as long as they adhere to the Scottish Outdoor Access Code.

By contrast, Scotland also has one of the most inequitable land ownership systems in the world, where just 0.008% of the population owns 50% of the land.

We are, in Scotland and across the planet, in a climate and nature emergency. The changing climate, and the ongoing and significant decline in Scotland’s nature, is testing the resilience of our landscapes and our seas.

Climate change brings more frequent storms, unpredictable rainfall, high winds and widely varying temperatures. Species and habitats are finding it harder than ever to survive, with changes in their environment happening much more quickly than they can cope with.

This is reflected in the ongoing declines in Scotland’s wildlife. In 2019, the State of Nature report showed that 11% of species were under threat of extinction, with 49% of species in decline and 62% showing strong changes. The 2023 report is not going to show an improving picture.

Without biodiversity, the landscape we’re accustomed to and love, and the ecosystems and services we rely on are changing and becoming much less reliable and resilient. Habitat loss and fragmentation on land and at sea is one of the biggest drivers of change.

It makes species and habitats much less flexible and it renders ecosystem services such as flood protection, water provision and pollination much more uncertain.

There is no doubt we need to turn this around. If we are to continue living the way we’re used to, and with the benefits of wildlife and nature we enjoy and promote to the world, we need to change the way we manage our land. We have no choice.

Management of our uplands, our woodlands, our farmland is all about stewardship. Land managers, farmers and crofters are stewards of the land on our behalf and for future generations.

Theirs is therefore a long term view – how can or should I treat this piece of land so I can hand it on in better condition to future generations?

This long-term view is also an ecological view.

Ecosystems are amazing – they can absorb huge amounts of change until suddenly they can’t. Ecosystems are also extremely complex. We don’t know when they will no longer be able to cope with change.

But once they change, change is dramatic and reversing or correcting that change takes an exceedingly long time, with exceedingly high costs. We only need look at the impact of cod stock collapse or desertification in other countries of the world.

If land managers and farmers are to adapt to the changing circumstances that we are all witnessing in the news and outside our front doors, they need to know not just what those changes will look like but also what they are expected to do about it and whether they be will be supported in adapting.

THIS is where a Just Transition is so vital. Unless they know, and unless they are brought into the conversation about future land use and future agriculture, they can’t plan and can’t adapt. The Just Transition Commission’s visit to Grantown-on -Spey in May 2023 was part of this process.

Planning environmental sustainability into any business is not an obstacle – it is a necessity and a responsibility. The responsibility of the business owner or manager is to ensure that the business can keep running into the long term.

If we look forward into the long term, a decade or more from now, we know that rainfall, wind speed and temperatures will be even more unpredictable. Wildlife will find it increasingly difficult to move to more suitable habitats or to stay where they are and survive.

Unless we make sure they can survive, or move, species will continue to disappear. And once they disappear, we lose pollinators, flood protection habitats such as peatlands and natural flood plains, grasslands and woodlands, healthy and productive soils.

The Just Transition is a social contract for the ecological transition we know is coming. Everyone must be involved, everyone must have their say and everyone must be clear on what is happening and what they need to do.

The climate targets, the upcoming nature targets and the Scottish Government’s clear vision for sustainable and regenerative agriculture are all very welcome. But we will only reach them if we work together and enable everyone to contribute and play their part.

Science is telling us we must act now. If we don’t, it is future generations who will lose out and who won’t experience the joy of Scotland’s landscapes and the wildlife that lives there.

Image credit: Sandra Graham

May 18th, 2023 by morag

The red squirrel is a true emblem of the Scottish countryside. To catch a glimpse of fiery red fur flickering up a tree and out of sight is a rare treat for most of us. There are only 140,000 red squirrels left in the UK, and more than 75% of these reside in Scotland. Their decline has been driven both by habitat loss and the introduction of the invasive non-native grey squirrel from North America. Grey squirrels outcompete reds for food and nesting sites, and spread squirrelpox, a virus which greys are immune to but which is deadly to reds. When greys move into a red squirrel territory, left unchecked, they can overthrow the native red population within 15 years.

Can we save Scotland’s red squirrels?

The grey squirrel exerts such pressure on the red squirrel that, if the current situation was left to play out, there would not be much hope for the native red in Scotland. The UK’s core red squirrel population in the Scottish Highlands is threatened by the expanding grey-only population in the Central Belt, and the remaining reds in South Scotland are consistently challenged by the influx of greys from Northern England.

Fortunately, there has long been abundant support for the red squirrel’s cause here in Scotland. Saving Scotland’s Red Squirrels (SSRS) was formed in 2009 by the Scottish Wildlife Trust and partners (the current partnership includes NatureScot; Forestry and Land Scotland; Scottish Forestry; Scottish Land and Estates; and RSPB Scotland; with funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund; Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority; and Aberdeen City Council). The establishment of this successful project brought together volunteer efforts from around the country and installed a coordinated, strategic approach to grey squirrel control on a landscape scale.

Now, 14 years on, grey squirrel control officers, with support from a dedicated network of volunteer monitors and trappers and grant-funded landowners, continue to work in priority areas, where the incursion of greys most threatens core red squirrel populations. Through this coordinated effort, SSRS demonstrates that it is possible to halt the regional decline of red squirrels and allow them to expand into new areas with targeted grey squirrel control.

So why not just let grey squirrels replace reds to fill the squirrel niche in Scotland?

Aside from wanting to save one of the nation’s most loved mammals for future generations to enjoy, there are other reasons to keep grey squirrel numbers under control. Unhindered, grey squirrel populations can reach densities eight or more times those of red squirrels. This is much more squirrel action than our native broadleaved woodlands can withstand, and it is at these densities that bark stripping becomes a real problem. Indeed, gangs of grey squirrels have been known to decimate whole woodlands! In England, where the majority of woodland cover is broadleaved, and where grey squirrel densities are much higher than they are in Scotland, tree damage costs the forestry sector an estimated £31 million annually.

Thanks partly to the grey squirrel’s preference for broadleaves, and partly to the work of SSRS, the conifer-dominated Scottish forestry sector is not yet feeling quite so nibbled. The Scottish Government, however, through its statutory forestry agencies, and in partnership with environmental NGOs, is actively engaged in landscape-wide native woodland restoration programs that will likely increase our national share of broadleaves. Initiatives such as Riverwoods – reconnecting the riparian habitat along our waterways, and the Alliance for Scotland’s Rainforest – revitalising the rare and important temperate rainforest ecosystem of the West Coast, could be put at risk by an unchecked grey squirrel population in Scotland.

What is next for SSRS?

Luckily, the SSRS program is a tried and tested approach already in place for keeping grey squirrel numbers down and stopping their spread into new areas. However, the program is now coming to the end of its latest round of funding and is in a Transition Phase. The Final Report from SSRS’ last major project phase (Developing Community Action) was released last month with a clear overarching recommendation that centrally coordinated, professional grey squirrel control and monitoring should be continued in the priority areas long-term to ensure a future for the red squirrel in Scotland. It is, however, no longer sustainable for this work to be delivered on short-term funding cycles with a charity responsible for leading delivery.

The draft Scottish Biodiversity Strategy to 2045 provides scope for invasive grey squirrel management to be continued as part of the Government’s plan for its delivery. Continuing this work would align with the Strategy’s commitments to continue effective species recovery programs, tackle invasive non-native species, and enhance forest and woodland biodiversity.

The re-shaping of SSRS therefore provides an opportunity for the Government, through its statutory agencies and other public bodies, to follow through on its biodiversity commitments by adopting a blueprint, developed over the lifetime of the project, to sustainably deliver a coordinated landscape-scale mosaic of grey squirrel control. Doing so will not only ensure the future of the iconic red squirrel in Scotland, but will also serve to protect our vulnerable existing and restored native woodland ecosystems and the vast assemblages of life that they have the potential to support.

Guest blog by Hazel Forrest, Species Advocacy Officer at the Scottish Wildlife Trust, May 2023.

Photo:

May 17th, 2023 by morag

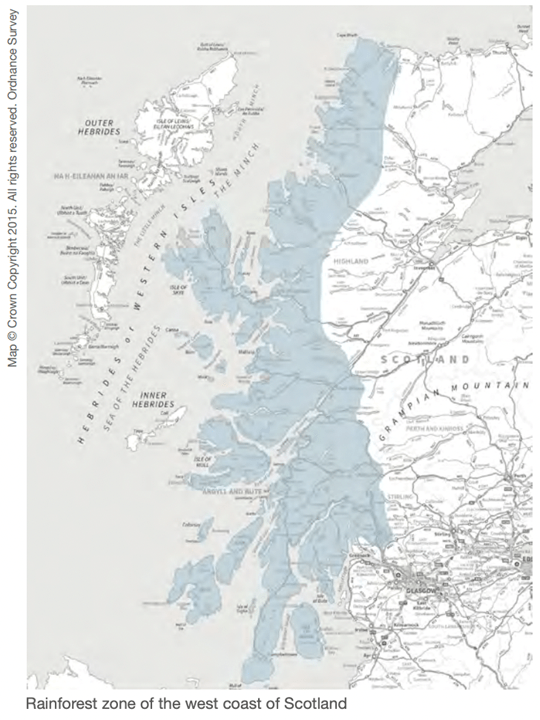

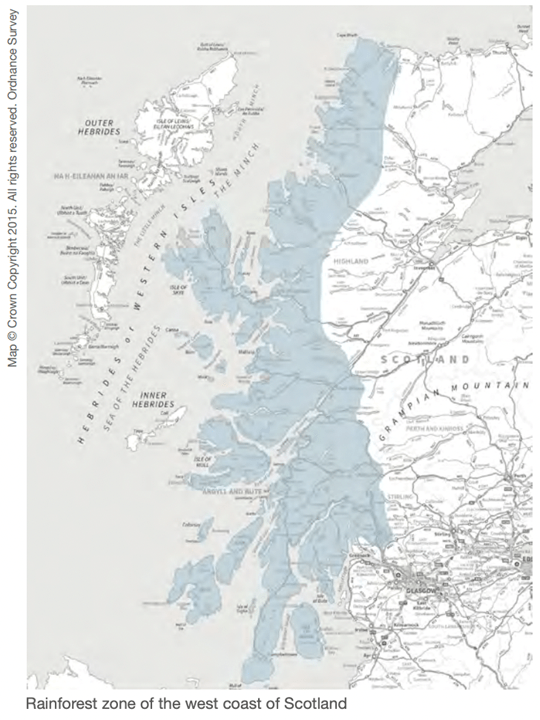

Rhododendron ponticum is one of the main threats to Scotland’s rainforest, alongside overgrazing by deer and sheep. An invasive non-native plant that is now well established in Scotland and the rest of the UK, it suppresses rainforest lichens and bryophytes, as well as the native trees which support them. The longer this issue is left unaddressed, the harder it will be to tackle and the more it will cost. This Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS) week, LINK’s Woodlands Group is calling for action to tackle this well-established INNS before it’s too late.

What’s the scale of the problem?

Rhododendron ponticum affects around 140,000ha of land in the rainforest zone (map below). This figure can be broken down approximately as follows:

- 30,000ha needs to be cleared urgently from within woodlands

- 24,000ha more needs to be cleared to ensure an effective buffer.

- 80,000ha of other habitat also needs cleared to prevent re-invasion.

When clearing Rhododendron ponticum it is critical to act at scale and over the long-term to ensure effective removal. This can deliver biodiversity benefits and create skilled local jobs as rhododendron control is labour intensive.

What support is available to tackle Rhododendron ponticum?

Rhododendron ponticum can only be cleared effectively at population level through ensuring the cleared area can be defended to prevent reinvasion. The current grants available for removal of rhododendron include the Forestry Grant Scheme administered by Scottish Forestry for woodland areas and the agri-environment climate scheme for open ground areas. A recent source of funding is the increased, multi-landscape and multi-year Nature Restoration Fund, which is a welcomed step that was announced by the Scottish Government in November 2021.

Why doesn’t the current approach work?

In Scotland, land managers have been removing Rhododendron ponticum for many years, but the spread continues. It is time to draw a line, evaluate and come up with a different approach. In some cases, current action fails because of the lack of a joined-up approach and the failure to follow up treatment to prevent re-invasion, resulting in wasted resources. The current approach is not adequate to eradicate rhododendron, and often only achieves piecemeal removal. The longer we wait to implement properly effective control the more rhododendron grows and spreads in the meantime. The main issues with the current approach that a report has identified include:

- the current limited priority control areas

- the need to apply for separate grants where rhododendron occurs both on open ground, in gardens, and in woodland making an already complex application process more difficult

- the short-term nature of the funding for an issue that needs to have a legacy strategy incorporated, to manage re-invasion

- the lack of recognition by policy makers and funders of the vital need to tackle rhododendron on a landscape, ‘whole-population’ scale, rather than a piecemeal approach. Even if rhododendron has been effectively suppressed in one area, if neighbouring land contains untreated rhododendron, then it will spread into the treated area. Time and public money are wasted.

What can be done?

To make a real difference a new approach is required with a step change in public funding and policy support. This starts with government and statutory agency leadership which needs to provide a clear objective to halt the spread of Rhododendron ponticum, and set out a strategic road map for tackling Rhododendron ponticum at scale and over the long-term. The review of future forestry grants and development of the future agricultural support package are clear opportunities to reshape public grants to encourage, facilitate and support landowners to deal with Rhododendron ponticum at landscape scale and with long-term legacy management.

For further details please read the Rhododendron in the Rainforest: Approaches to a growing problem report.

Guest blog by Arina Russell, Policy and Advocacy Manager for the Woodland Trust.

May 16th, 2023 by morag

We at Plantlife are encouraging more and more people to embrace wilder lawns and enjoy all the benefits that biodiversity has to offer with the No Mow May campaign. Officially launched in 2019, Plantlife’s No Mow May urges those of us with gardens to take a pause for the summer and put our mowers away, making space on our lawns for wildflowers, pollinators, and other wildlife to thrive.

With the climate and nature crises on our doorstep, we are often looking for that one thing we can do to help. There are over 20 million gardens in the UK; consider that by simply “doing nothing for nature”, even the smallest grassy patches can help add up to an area of land equivalent to the size of East Ayrshire. A more relaxed mowing regime is just one way to contribute to combating these crises.

Nicola Hutchinson, Director of Conservation at Plantlife puts it plainly, “Wild plants and fungi are the foundation of life and shape the world we live in. However, 1 in 5 British wildflowers is under threat and we urgently need to arrest the losses. With an estimated 23 million gardens in the UK, how lawns are tended makes a huge difference to the prospects of wild plants and other wildlife. The simple action of taking the mower out of action for May can deliver big gains for nature, communities, and the climate. So, we are encouraging all to liberate lawns as never before.”

In Scotland naturally our wildflowers bloom later in May compared to the rest of the UK, but that is ok, as long as we give our wild plants a chance to grow for at least one month. In fact, Plantlife guidance recommends a balanced approach to lawn care throughout the year with the collection of lawn cuttings after each time you mow. Their team of wildflower experts encourage you to incorporate a mixture of shorter zones for sitting out in the garden, and taller, more structured areas which will help boost overall biodiversity.

No Lawn? No worries! Plantlife has several ways you can still participate in the movement of increasing biodiversity, including making a mini meadow in a window pot.

So, get out there and free your lawns by doing nothing for nature this May, and beyond!

Erin Shott, Communications and Policy Officer at Plantlife Scotland

May 2nd, 2023 by morag

Summary:

There is a very strong global evidence base showing that Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs) have a positive impact ecologically and can support the fishing industry. HPMAs, also known as marine reserves or no take zones, act as nurseries and refuges and as such benefit marine species and habitats both within the protected area and outside them.

Evidence from across the world shows that, on average, twice as much total fish biomass and fish density is found in the protected area than outside. These benefits can happen quickly, within a few years of protection, and can have a ‘spillover’ effect into surrounding waters.

To maximise both conservation and socio-economic benefits, HPMAs should be bordered by buffer zones to benefit low impact fishers. With such zones HPMAs can benefit sustainable fishing, and those engaged in it, while at the same time helping build up fish and other marine species populations across the wider sea and for future generations.

However, success will depend upon a collaborative approach with all stakeholders, including local communities, fully involved and engaged with support, access to advice and scientific evidence and independent scrutiny. The Scottish Government’s Just Transition outcomes are key in delivering success for coastal and island communities as well as Scotland’s marine biodiversity.

Background

The marine environment is one of Scotland’s greatest assets and a vital resource for communities who rely on marine activities like fishing and wildlife tourism. However, evidence shows a continuing decline of our marine ecosystems, impairing their ability to provide the life-sustaining benefits we all depend on.

In the Bute House Agreement, the Scottish Government committed to designate at least 10% of our seas as “Highly Protected Marine Areas” (HPMAs). HPMAs are areas of the sea that are placed under strict protection to support ecosystem recovery and protect against climate change. This is in line with internationally agreed standards for nature recovery and resilience (e.g. Global Biodiversity Framework Target 3), and follows the EU’s own 10% target for strict protection.

The effects of strict protection at sea have been widely documented globally, and growing evidence highlights the ecological and socioeconomic benefits of these marine reserves or no-take zones. The following briefing provides a non-exhaustive summary of the science available regarding HPMAs in the world.

Ecological benefits within HPMAs

Various HPMAs can be found worldwide, and research demonstrates their benefits on marine life within and outside their boundaries. The MPA guide helpfully provides a map of 226 MPAs, 114 of which are equivalent to the proposed Scottish HPMAs.1 HPMAs are equivalent to “marine reserves”or “no take zones” and have been abundantly studied across the world, in both tropical and temperate waters. Hundreds of surveys, often summarised in global or regional studies, show that protecting the marine environment from damaging activities leads to a sharp increase in abundance, average body size and biomass of marine species.2

A 2019 synthesis of current scientific evidence shows that HPMAs can provide greater benefits than lighter forms of protection. Placing areas of the sea under strict protection allows marine species to recover, by providing them a refuge to grow, age and reproduce. In their analysis of 24 no-take zones in the highly pressurised Mediterranean Sea, Giakoumi et al. (2017), demonstrated that high levels of protection have significant ecological benefits for fish biomass and equally positive effects for fisheries’ target species.3 The total fish biomass and density were on average twice as much in fully protected areas than outside. The study also highlighted that there was no difference in total fish biomass between partially protected and unprotected areas.

Ecological benefits can be observed within no-take zones only a few years after their creation, with increase in populations within two to five years.4 The impressive case of the Cabo Pulmo protected areas, in the Gulf of California, showed an almost five-fold increase of the fish biomass only a decade after its creation. Closer to home, research carried out in the small no take zone in north Lamlash Bay since 2010 shows a dramatic improvement – measured biodiversity has increased by 50%, while the populations of commercially important species are 2-3 times higher within the no take zone. King Scallop, (Pecten Maximus) populations have increased almost four-fold, with the scallops being older and producing more eggs. Surveys undertaken between 2012 and 2018 highlight similar effects on European lobsters. The experience in Lamlash Bay clearly demonstrates the potential spillover benefits to Scottish fishers from even small areas of strict protection.

Another great example of a successfully implemented HPMA is the French Marine Park of la Cote Bleue, created in 1982. The no-take zone of Carry-le-Rouet was created in 1983 and a second no-take zone, the reserve of La Couronne was created in 1996. Local fishermen played a key role in the creation of La Couronne HPMA, and the management of the two no-take zones: continuous dialogue between local authorities and fishermen led to management measures beyond the Carry-le-Rouet HPMA boundaries. In their study of six no-take zones in the Mediterranean Sea, Harmelin-Vivien et al (2008)5 confirmed an increase in the abundance, biomass and size of fishes inside marine reserves. They observed that the average biomass within the marine reserve of Carry was 16.3kg, compared to 2.4 kg outside the area.

Ecological and socioeconomic benefits beyond HPMA boundaries

Research worldwide6 demonstrates that, if implemented and managed well, HPMAs can have positive effects beyond their boundaries, supporting marine activities such as fisheries or tourism. As populations within the HPMAs increase in size, and individuals grow larger and live longer, they can reproduce more. This enhanced reproductive potential can then lead to the replenishment of populations adjacent to the no take areas – a “spillover” effect to fished areas.7 The spillover effect arises firstly, through the export of eggs and larvae outside the marine reserve, and secondly from the movement of juvenile or adult animals from the no take zone to adjacent waters. Studies in the Mediterranean confirmed the role of marine reserves in sustaining local fisheries for commercial species such as the spiny lobster, Palinurus elephas. Harmelin-viven et al (2007), observed a spill over effect in all the reserves they studied, thus demonstrating the long-lasting effects of strict levels of protection.

Studies of Highly Protected areas from around the globe reflect the financial benefits for local communities from recreation and tourism. The network of marine reserves in New Zealand is often cited as a successful case. The country pioneered marine reserves by establishing its first no-take zone in 1977. Beyond observing ecological benefits and an increase of the biomass within the reserves, researchers highlighted the sharp increase in popularity of the protected areas. The first no-take zone created became a major tourist attraction and is estimated to be worth several million dollars per year to the district.

Spillover of fish was measured at up to 1959m from one of the reserve boundaries, and averaged over 500m across all the sites (Harmelin-Vivien et al, 2008). Evidence shows that the extent of the spillover effect depends on the pressure in the adjacent waters. Indeed, the spillover effect is predicted to be “smaller” in areas where adjacent waters are highly pressured.

However, HPMAs cannot be considered in isolation of other marine policies and management processes. Pauly et al. 2002 states that: “Marine protected areas (MPAs), with no-take reserves at their core, combined with a strongly limited effort in the remaining fishable areas, have been shown to have positive effects in helping to rebuild depleted stocks.”8

In order to maximise the conservation and economic benefits of HPMAs, LINK recommends that no take zones should be buffered by low impact fisheries zones, prioritising sustainable fishers who can benefit from the immediate spillover effect. Creating buffer zones would help protect low impact fisheries from displacement by giving them preferential access to waters. This would be part of meeting the Scottish Government’s Just Transition outcomes, underpinned by the 5 principles for a Just Transition, as set out by the Just Transition Commission in 2022.

A collaborative approach with all stakeholders is essential to achieving conservation objectives, and to build support among stakeholders and wider society. LINK believes that successful engagement must include improved stakeholder participation with clear expectations, wider strategy and support mechanisms for affected activities, use of best available science and independent scientific scrutiny of proposals.

For more information, contact:

Calum Duncan, Convener of LINK’s Marine Group or Fanny Royanez, LINK’s Marine Policy Officer.

Image: Calum McLennan

Footnotes:

- Based on IUCN definition of MPA fully protected areas means no extractive or destructive activities are allowed.

- Biomass can be defined as the total quantity or weight of organisms in a given area or volume.

- Giakoumi, S., Scianna, C., Plass-Johnson, J. et al. Ecological effects of full and partial protection in the crowded Mediterranean Sea: a regional meta-analysis. Sci Rep 7, 8940 (2017).

- DOI: 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00189-7 “Increases in protected populations are often rapid, frequently doubling or tripling in two to five years”.

- Harmelin-Vivien M, Le Diréach L, Bayle-Sempere J, Charbonnel E, García-Charton JA, Ody D, Pérez-Ruzafa A, Reñones O, Sánchez-Jerez P, Valle C (2008) Gradients of abundance and biomass across reserve boundaries in six Mediterranean marine protected areas: Evidence of fish spillover? Biological Conservation 141:1829-1839

- Effects of Marine Reserves on Adjacent Fisheries; Evidence that spillover from Marine Protected Areas benefits the spiny lobster (Panulirus interruptus) fishery in southern California; Benefits beyond boundaries: the fishery effects of marine reserves.

- Study vindicates the benefits of no-fishing zones on the Great Barrier Reef; Benefits beyond boundaries: the fishery effects of marine reserves.

- Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Guénette, S., Pitcher, T. J., Sumaila, U. R., Walters, C. J., … & Zeller, D. (2002). Towards sustainability in world fisheries. Nature, 418(6898), 689-695.

April 7th, 2023 by morag

What are “Highly Protected Marine Areas” (HPMAs)?

Highly Protected Marine Areas are areas of the sea that are placed under strict protection to support ecosystem recovery and protect against climate change.

The Scottish Government has committed to giving a small proportion – just 10% – of our seas this strict protection. This is in line with international recommendations for nature recovery and resilience and follows the EU’s own 10% target for strict protection.

HPMAs are well-established globally and proven to have ecological benefits, which in turn can benefit fishers. The success of the ‘no-take zone’ (an area where no fishing is allowed, equivalent to an HPMA) of Carry-le-Rouet in the French Mediterranean, created in 1983, led to the fishing industry playing a key role in the establishment of a second HPMA nearby, the reserve of La Couronne.

Why do we need HPMAs in Scottish seas?

We are facing a twin nature and climate crisis, and nature’s recovery must be central to government priorities and policies. In its latest report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned that the impact of climate change was increasingly irreversible and called for every country and sector to take drastic action on all fronts to tackle the climate crisis. Last year, the UN Secretary General declared an “Ocean Emergency” and called for collective and urgent action to restore marine life.

In Scotland, the health of our seas is vital for communities who rely on marine activities like fishing and wildlife tourism. However, evidence shows a continuing deterioration of marine ecosystems, and some of our living seabed habitats, such as seagrass, have suffered from catastrophic decline. UK administrations have collectively failed to achieve 11 out of 15 of the ‘Good Environmental Status’ targets set by the UK Marine Strategy, with seabird populations in particular continuing to decline.

Scotland’s Marine Assessment 2020 identified climate change and fishing activities that drag heavy nets across the seabed or through the water as the key pressures facing marine biodiversity.

If implemented alongside other sustainable management measures, HPMAs would provide Scotland with core zones for ecosystem recovery, helping us address the climate and nature crises and increasing our seas’ resilience to climate change. For thriving seas with healthy fish populations, we need an effective marine planning system that protects key areas, including HPMAs, so that Scotland’s seas can support species, habitats and communities.

How do HPMAs work?

HPMAs provide strong levels of protection to the marine environment by prohibiting all impacting or damaging activities in a small number of designated sites. Activities that remove or damage natural resources or that dump materials and pollutants in the sea are banned. The specific rules for Scotland’s HPMAs will be determined by the Scottish Government.

The recently published global MPA Guide provides a helpful summary of what activities are or are not compatible with fully and highly protected areas.

What are the benefits of HPMAs?

The ecological effects of HPMAs have been widely documented globally. A 2019 study showed that HPMAs can provide greater benefits than other types of Marine Protected Areas.

HPMAs provide dedicated havens for vulnerable and depleted marine life to recover. Allowing fish, shellfish and other species to flourish in a fully protected area also benefits the many people and activities that rely upon healthy seas. The benefits from these areas overflow into surrounding waters, increasing the abundance and resilience of sea life, benefitting low impact fishing.

Analysis of the 24 no-take zones in the Mediterranean sea demonstrated that high levels of protection have significant ecological benefits for fish biomass and equally positive effects for fisheries’ target species. The total fish biomass and density were on average twice greater in fully protected areas than outside.

The community-led no take zone in Lamlash Bay off the Isle of Arran is Scotland’s only strictly protected area equivalent to a HPMA (as proposed in the recent Scottish Government consultation) and demonstrates on a small scale their potential for success. Biodiversity in the bay has increased by 50% since 2010, and the king scallop population more than trebled between 2013 and 2019. This has increased opportunities for low impact fishing and for scallop hand diving, benefitting the local economy.

Where will HPMAs be placed?

The Scottish Government is responsible for designating Scotland’s HPMA sites. Proposals will be informed and assessed by Scottish Government conservation advisors, NatureScot and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee, who will suggest whether they meet the criteria to be designated as HPMAs. Proposals from organisations and members of the public will also be invited (‘third party proposals’), which will be assessed in the same way.

It is our view as members of Scottish Environment LINK that coastal, island and fishing communities should be closely involved in the process of designation as equal partners. An effective HPMA network should be spread across both inshore and offshore waters, in areas that have been degraded or that have the potential to recover to a more natural state, and should be designed to support both ecological and social sustainability.

Can HPMAs exist alongside a viable fishing industry?

Yes – HPMAs can support a sustainable fishing industry. Where there are designated ocean recovery zones, fish stocks will increase with spillover effects in neighbouring areas. The example of French fishermen working towards additional HPMAs after experiencing the benefits of no-take zones shows that this approach can bring significant benefits to industry itself.

Where else has HPMAs?

HPMAs are a key tool to enable the protection and recovery of marine ecosystems. Globally, the number and coverage of HPMAs are increasing. The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 sets a target of ‘strict protection’ of 10% of the EU’s seas by 2030.

Various HPMAs can be found worldwide, and research demonstrates their benefits on marine life within and outside their boundaries. The MPA guide helpfully provides a map of 226 MPAs, 126 of which are under high levels of protection.

April 5th, 2023 by morag

No-one knows more than the communities living around Scotland’s vast coastline how important and stunning our seas are. The health of the ocean, and particularly the seabed, is at the heart of sustaining communities reliant on wildlife tourism, fishing and aquaculture.

The ocean regulates half the oxygen we breathe. Our lives literally depend on it. It has absorbed more than 90 per cent of all the excess heat produced by society in recent decades. Despite this, the seabed has unfortunately been out of sight out of mind for most.

Globally, we’re in the midst of an ocean emergency. Areas of the ocean are becoming more acidic meaning shell-forming creatures struggle to create their shelters, other areas are becoming deoxygenated dead zones, and ocean nature is declining due to overfishing, ocean warming, inappropriate development, and a soup of plastic and invisible poisonous chemicals.

Despite this, all governments of the UK spectacularly failed to ensure our seas were in good environmental status by 2020, failing 11 of 15 targets including halting the loss of nature at sea.

Nine years after the first assessment required of the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010, Scottish Government scientists and advisers again highlighted that the condition of most of Scotland’s seabed was of great concern. Some living seabed habitats have declined by over 90 per cent in the space of only a few years.

The Bute House Agreement between the Scottish Government and Scottish Greens made welcome commitments to complete planned marine conservation measures, modernise inshore fisheries management more widely and commit to designating at least ten per cent of Scotland’s seas as Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs).

Such areas have proven successful worldwide. They provide oases for vulnerable and depleted marine life to recover. Allowing fish, shellfish and other species to flourish in a fully protected area also benefits the many people and activities which rely upon healthy seas. The benefits from these areas overflow into surrounding waters, increasing the abundance and resilience of sea life. This overflow can benefit nearby low-impact fishing, such as angling, creeling and hand-diving, and other fishing beyond.

Protected areas also provide excellent places for people to simply celebrate their local blue space, to enjoy it and to learn about the role and value of ocean ecosystems. An excellent example of this is the pioneering Lamlash Bay Community Marine Conservation Area. Rolling out more such areas requires a holistic and integrated approach. The proposed HPMAs would need to protect a mix of inshore and offshore waters so that the benefits and trade-offs are spread around Scotland’s coasts.

The ocean emergency is real. Our seabed habitats are under threat, and populations of seabirds continue to decline. Highly protecting a modest ten per cent of the seabed from extractive, construction, and depositional activities, could help provide multiple wider benefits if managed well, and bring all communities of place and interest onboard.

HPMAs provide core ocean recovery zones with multiple benefits; they increase biodiversity, including of living reefs, lobsters and scallops, and increase the storage of carbon in living animals and seaweeds, and the seabed itself (blue carbon). They also improve protection of the coastline from storm damage and provide ocean beacons for research and enjoyment. HPMAs would create vibrant blue spaces for kayakers, wild swimmers, beach walkers, rockpoolers, divers, wildlife spotters and others to enjoy.

It is crucial that HPMAs are placed strategically to maximise community benefits. This includes having surrounding buffer zones for low-impact fishing, into which fish and shellfish can overspill, and identifying and protecting zones for appropriate levels of fishing in the wider seas.

Everyone wants to see healthy seas supporting abundant wildlife and thriving coastal communities. Done well, HPMAs can provide a win-win for all with a stake in the health of the ocean.

Join the campaign for HPMAs at scotlink.org/oceanrecovery.

Calum Duncan is Head of Conservation Scotland at the Marine Conservation Society, and convenor of Scottish Environment LINK’s marine group

This blog was published in the Friends of the Scotsman, on Tuesday 4 April 2023.

Image credit: Calum Duncan

March 28th, 2023 by morag

On his election as First Minister, Scottish Environment LINK has written to Humza Yousaf to congratulate him on his appointment, with the letter signed by 31 members of the environmental coalition. The letter urges strong leadership and action in a number of crucial areas, while acknowledging the progress already made in recent years, notably through the Edinburgh Declaration on biodiversity.

Scotland faces twin environmental crises of nature loss and climate change. The latest IPCC report, issued this month, made clear that humanity requires urgent action to protect our environment, and underlined the importance of restoring nature as part of this effort. A healthy environment with rich and diverse nature is fundamentally important to the health, wellbeing and prosperity of Scotland’s people. However, Scotland has suffered a high level of historic nature loss and this is accelerating further, with 1 in 9 species at risk of national extinction.

The letter calls on the First Minister to reaffirm the Scottish Government’s commitment to our natural environment across the following areas:

- Nature protection and restoration

- Farming and forestry

- Circular economy

- Just Transition and human rights

Scottish Environment LINK is the forum for Scotland’s voluntary environment community, with over 40 member bodies representing a broad spectrum of environmental interests with the common goal of contributing to a more environmentally sustainable society.

Read the letter and list of signatories

Image credit: Sandra Graham

March 9th, 2023 by Miriam Ross

At the end of last year the European Environment Agency (EEA) published the report, ‘Circular Economy policy innovation and good practice in Member States’, which highlights areas of progress in countries across Europe. As well as good examples, the report examines the barriers and challenges which are shared across EU countries.

In this blog I have picked out some examples that caught my attention, as they highlight things Scotland could be doing, but isn’t.

It is no secret that consumption based targets with linked delivery plans are at the heart of Scottish Environment LINK’s, and our members’, circular economy demands.

The EEA report finds: ‘The number of EU Member States that use consumption based indicators, such as RMC (Raw Material Consumption) and the material footprint, has increased considerably to 12 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, FinIand, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Sweden, Slovakia), compared to just five countries at the time of the last survey in 2019.’

And ‘…. early CE [circular economy] adopters, such as Belgium, Finland and the Netherlands, are following up their first policies (2016–2017) by active (sectorial) stakeholder involvement through, for example, strategic/transition agendas to identify finance and implement concrete CE measures’.

So Scotland, which in the past has been counted among the forerunners in moving towards a more circular economy, has some catching up to do. With Scotland’s circular economy strategy Making Things Last published in 2016, we should be well on the way to comprehensive sectoral plans laying out concrete agendas. Although work has been going on to support circularity in different sectors, a comprehensive approach has been sorely missing.

The forthcoming Circular Economy Bill and route map bring some hope, but the danger is that time frames stretch and in the meantime the Scottish economy continues to hoover up raw materials at a rate that is incompatible with global carbon and nature goals and Scotland’s position on international justice. We need the Circular Economy Bill to set consumption based targets as soon as possible, following the leaders in Europe. Scotland’s Material Flow Accounts show us that our raw material consumption is currently nearly treble what is widely considered a sustainable level.

We often hear that it is pointless setting targets without the plans to deliver them. I would argue that the targets are needed to drive the development of the plans. Scotland did not wait for delivery plans to set the climate change targets – the targets were set and the delivery plans have followed, in the shape of the Climate Change Plans. The same approach should be used for addressing our consumption impacts.

There are many innovative ideas, examples of good practice, and individuals willing to be involved in developing plans to reduce our material consumption. If the Scottish Government is unsure about pathways, measures set out in Scotland’s Circularity Gap report add up to a reduction of about 43% in our material and carbon footprints.

Other specific initiatives which I noted from the report include the following.

Procurement: In Denmark, there is mandatory use of total cost of ownership in state procurement for specific product groups, so that the running costs, maintenance costs and disposal costs are all factored in. In this way, the focus will shift from the acquisition price to costs throughout a product’s lifecycle. The requirement will initially apply to 25 product groups with further groups to be added. In France, legislation requires that a percentage of goods acquired annually by central and local authorities must come from reuse or incorporate recycled materials. There is list of products to which this applies, including laptops, paper, desk furniture and textiles.

Construction: In Denmark, the government introduced a decreasing mandatory threshold limit for climate footprints based on whole life-cycle analysis – the emissions associated with all phases of the building’s life (material sourcing, construction, use and after-use) for new buildings in the Building Code. Luxembourg introduced an obligation to submit a digital material inventory for new construction.

Repair: The Austrian Repair Bonus introduced a voucher which provides a 50 % discount (with a limit) to consumers for repairs to electrical and electronic devices commonly used in households. In the first few months of the scheme, 63,400 vouchers had been cashed in 2,300 participating repair businesses.

Reuse: In Flanders, Belgium, in March 2022, about 80 organisations signed the Green Deal Anders Verpakt. Stakeholders are shifting the focus from increasing the collection and recycling of waste to prevention, omitting packaging, and the reuse of packaging. The Green Deal focusses on a chain approach in which companies, governments, knowledge institutions and citizens work together towards common objectives.

The impact of implementing measures like these in Scotland would be significant. Scottish Environment LINK wants to see some real change on the ground in Scotland that will address our over-consumption. We need consumption targets and transition sector plans to drive a comprehensive approach, but we also can and need to get one with more and bigger concrete measures if we are going to make the difference that is so sorely needed.

By Phoebe Cochrane, sustainable economics officer

Photo: Copenhagen by Svend Nielsen on Unsplash

February 16th, 2023 by Miriam Ross

By Alistair Whyte, head of Plantlife Scotland and convenor of Scottish Environment LINK’s wildlife group

The natural environment is important to 92% of Scots, according to a recent poll commissioned by Scottish Environment LINK. That’s a high figure, but it didn’t come as a surprise to me. Surely almost all of us have a sense of pride in Scotland’s landscapes and wildlife – in our eagles, pine forests, and wave-battered coastlines.

I think our connection to Scotland’s wildlife runs deeper than those picture-postcard images. Nature and culture are intrinsically linked here, not least because the way we manage the land has given rise to some of our most wildlife-rich habitats. What we eat and drink is bound up with the health of the land and seas that produce it. And the events of the last three years brought into stark relief the importance of accessible natural spaces for everyone.

This means it can be hard to get our heads around some depressing statistics about the state of Scotland’s environment. But the science points towards a nature crisis, right here. Survey after survey tells us that our wildlife is not faring well. And the Biodiversity Intactness Index, an internationally-adopted measure of biodiversity, puts the UK in the lowest 12% of countries. Whilst Scotland performs better than the other UK countries, all four countries sit close to the bottom of this biodiversity league table. Put simply, Scotland’s wildlife and habitats are a shadow of their former selves.

For a long time, Scotland’s environmental groups have been calling for a meaningful plan for nature recovery. This plan must be ambitious, and must focus not just on nature protection, but, crucially, on restoration. Our battered, beleaguered ecosystems need to be rebuilt if they are to function properly.

Restoring ecosystems means restoring all the building blocks of those ecosystems – which means we need a targeted programme of species recovery to sit alongside these ambitious ecosystem restoration proposals.

In December of last year, the Scottish Government published its draft Scottish Biodiversity Strategy to 2045. The strategy outlines key outcomes to be achieved by 2045 – but for these high level outcomes, and the series of priority actions which follow, more detail about how they’re going to be achieved is critical, alongside targets which will demonstrate success. These targets must be legally-binding, and integrated into all government delivery. If it lacks this accountability, the strategy stands a good chance of gathering dust on a shelf in the library of good intentions.

Greater ambition on species recovery is essential – without this, there’s a real risk that, even if our ecosystems recover, some of our most iconic species will slip away. We can’t allow this to happen.

All this talk of targets and plans can seem a million miles away from the glint of an Atlantic salmon running a Highland river, or the rich, vibrant patchwork of the Hebridean machair. But the fate of those things rests hugely on the actions of government over the next few months and years. Scotland could be a world leader in biodiversity recovery. For a nation that values its natural environment so highly, that feels like a pretty good place to aim.

This article was first published in the Scotsman on 16 February 2023.