Independent councillor for Lerwick South on Shetland Islands Council Dr Jonathan Wills argues that current plans risk creating conservation ‘islands’ in a sea of escalating industrial development…

Independent councillor for Lerwick South on Shetland Islands Council Dr Jonathan Wills argues that current plans risk creating conservation ‘islands’ in a sea of escalating industrial development…

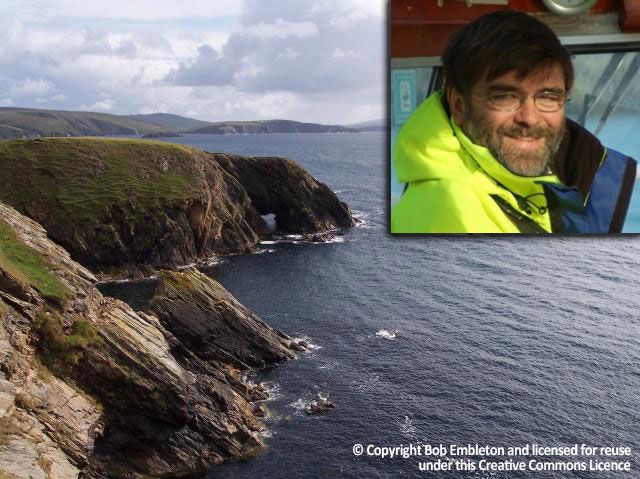

The crew of an alien spacecraft, entering the Earth’s atmosphere over the north of Scotland, could not fail to be impressed by the beauty of Shetland, Orkney and the Hebrides.

Being even more sophisticated and better equipped than most civil servants, our visitors from Planet Dork would immediately recognise that these islands are part of an intricate, varied and very fragile ecosystem. Sensors on board the spaceship, as it skimmed southwestwards from Muckle Flugga to the Mull of Kintyre, would also notice that the most biodiverse and productive part of the ecosystem lies under the sea (something the seers of St Andrews House have not yet registered). The Mekon piloting the ship would probably clap a preservation order on the lot, for aesthetic if not economic reasons, before flying on to have his wicked way with the cities of the plains between the Ochils and the Pentlands.

The Mekon? That dates me. He was the sinister alien in the Eagle comic’s ‘Dan Dare’ strip in the 1950s. Sometimes I feel the Mekon’s already taken us over. It’s more than five years now since the new Scottish Government decided not to go ahead with an imaginative plan to create Scotland’s first National Marine Parks, apparently because some rich fishermen didn’t like the idea (and also, perhaps, because the Lab-Lib Coalition at Holyrood had promoted it). Instead, we’ve had a series of Special Areas of Conservation and Marine Protected Areas. These are all very well and worthy but, when I recently re-read the papers I wrote in 2006, advocating the proposed Shetland National Marine Park, I found that the argument for much larger protected areas was stronger than ever.

The basic problem, underwater, is that we’re creating conservation ‘islands’ in a sea of escalating industrial development, just as we’ve been doing on land for such a long time. Rather than saying “this place is beautiful, special and we must preserve as much of it as possible if we want to have thriving fishing and tourist industries for our grandchildren”, the attitude seems to be “if you want to keep some little bits pristine then you’ll have to make the case for it and ensure the fishermen, the fossil fuel industry and the cable layers are kept happy”. This partial, piecemeal approach to marine planning repeats the errors of the terrestrial planning industry which (and I quote a planning officer whom I recently questioned about the new Planning Act) always has a “presumption in favour of development.”

Piecemeal conservation isn’t conservation at all, because it fails to recognise that habitats such as the luxuriant Shetland kelp forest and its amazing caves, encrusted by a riot of corals and creatures that rival the Great Barrier Reef, are part of a vast ecosystem fringing western Europe from southwest Ireland to northern Norway. Offshore, where it’s too deep and dark for seaweed, there’s even more biodiversity, as the oil industry’s own surveys have revealed over the past 40 years. If you break it up into isolated bits you’re likely to damage it by far more than the sum of the fragmented pieces.

Of course we need somewhere for the fishermen to fish, but it would be in their own interests if we kept heavy trawls and scallop dredgers out of the 12 mile limit. Of course we need undersea cables, not least to develop wind, wave and tidal power on the islands, and the cable tracks would add to the area of no-catch zones where fish stocks might recover after a century of over-fishing, without the risk of pollution that comes with oil platforms and floating production and storage vessels. Until renewables are far more developed than they are today, we also need oil and gas, but at what cost to the tiny animals that live on and under the seabed, and which in turn are food for commercial fish?

It’s the developers who should have to argue the case for making a hole in the blanket of conservation, a blanket that ought to be in place already, if we’re serious about “sustainability”. At this rate there’ll soon be more holes than blanket. If you doubt this, look at a chart of the platforms, pipelines, submarine cables and heavily trawled fishing grounds in the North Sea. It looks like a painting of a rat’s nest by Jackson Pollock.

The ‘presumption in favour of development’ is epitomised by what’s happening in the final phase of the fossil fuel industry on the “Atlantic Frontier”. As I write this, I’ve been asked to comment on the Westminster Government’s draft oilspill contingency plans[1] for the west Shetland oil and gas fields, in water almost as deep as, and considerably stormier than, the Gulf of Mexico. The LibberTories say it’s acceptable that the only insurance cover for a Macondo-style blowout west of Shetland is a voluntary scheme run by the companies, with a kitty of just $250m. That wouldn’t pay the flights and hotel bills of the workers who’d have to wipe clean Shetland’s 1600-mile coastline of beaches, cliffs, caves and kelp forests, if and when the big one happened. But it’s OK, folks – the plan says if the cost were more than $250m ($2.5bn is not unlikely) then the victims of pollution would be able to sue the miscreants in the courts. Oh, goody! If the Amoco Cadiz and Exxon Valdez cases are anything to go by, it could take 10 to 20 years to settle, by which time some of the claimants will, conveniently, be dead.

There oughta be a law.

(This article was submitted end of November 2012).