Guest blog by WWF Scotland Policy Advisor, Mario Ray

© naturepl.com / Toby Roxburgh / WWF

The UK’s fishing industry has long been a fundamental part of vibrant coastal communities, providing livelihoods to many and food to feed us, from Cullen Skink on a cold winter’s evening, to whole grilled mackerel with lemon and garlic, or scampi and chips by the sea.

However, our seas, wildlife and the fishers whose livelihoods are dependent upon healthy marine ecosystems, are suffering. International marine biodiversity targets have not been met and the UK, as a whole, has failed to meet 11 out of the 15 indicators for achieving Good Environmental Status. Commercial fishing continues to be the most widespread pressure on the marine environment but it also has real opportunity to provide solutions and help recover our seas if done sustainably.

Meanwhile, for fishers, uncertainties regarding market access and the increase in fuel prices have resulted in unemployment and family upheavals; with some fishers tying up their boats for good and having to relocate their families in search of alternative employment. It is a turbulent time for the fishing industry and they need to be given certainty.

The Discard Ban

For many years one of the key concerns over the impacts of fishing on biodiversity was the wasteful nature of many fisheries in which significant amounts of unwanted fish were dumped back into the sea, a process known as discarding.

A discard ban was introduced with the hope that it would incentivise more selective fishing and less discarding. The rule made sense, but it was poorly managed and enforced with little evidence of widespread uptake. The fact that such a policy which required fishers to significantly change the way they operated, was not accompanied by robust monitoring to ensure a level playing field, gave it little chance of success from the outset; and many saw this coming.

© Alexander Mustard / WWF-UK

How do you catch a haddock without catching a cod?

In the North Sea a lot of the fish we catch are part of mixed fisheries – fish like haddock and cod tend to swim together (unlike mackerel, which swims higher up in the water column as a more exclusive and fast-moving shoal).

The problem for fishers who target these mixed fisheries is that the quota for one fish (e.g. cod), might be very low or even set to zero, while the quota for another (e.g. haddock) might be much higher. So how do you catch a haddock without catching a cod?

© Alexander Mustard / WWF-UK

We are constantly learning new things about the UK’s marine life. If you chase a haddock, for example, it will likely swim up towards the surface. If you chase a cod, it will swim down to the safety of the seabed.

If you have a fishing net with larger ‘escape panels’ in the roof of the net – then you’ll not catch many haddock, but you will catch cod. Other fish can take advantage of their shape, e.g. sole, which will squeeze through fish nets with horizontal slits. Using highly selective fishing gear (that is designed taking into account fish behaviour, preferences, shape etc.) can help catch the fish you want and avoid the ones you don’t.

However, an obstacle to investing in highly selective fishing gear is that it comes at a cost. The cost of the gear itself which can run into the tens of thousands and the cost of some marketable fish that pass through the ‘selective’ gear. With very little monitoring at sea, the impact of the discard ban was not clear. While some complied and invested in new gear, others continued to operate with business as usual. Without the level playing field, which would have been achieved with robust monitoring, it created a competitive advantage for those that continued to discard.

A game-changing technology is ready for roll-out

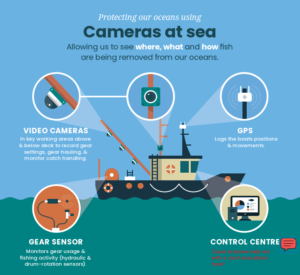

The good news is there is a tried and tested solution that’s a win-win-win for wildlife, fishers and you: Remote Electronic Monitoring (REM) with cameras.

REM is a powerful and cost-effective tool that answers three fundamental questions: where boats are fishing, when and how they are fishing and most importantly, what is being removed from the water – target and non-target species. With a much clearer picture we can improve fisheries management, help prevent overfishing and ensure fishing is sustainable for future generations.

Design and illustration by edharrison.co.uk

People are increasingly concerned with the provenance of their seafood, and the impact it has on marine wildlife. The best tool to help de-risk fisheries and give green light for access to more retailers is REM with cameras. This technology enables fishers to demonstrate to the public and retailers that they are operating in a sustainable way, using best practice and highest levels of selectivity.

REM would also empower fishers by putting them at the heart of the data collection process, bridging the gap between them and fisheries managers. Fishers spend a significant amount of their lives at sea and claims that catch quotas are out of touch with what they are seeing in their nets need to be addressed. The ‘fish-counting’ cameras provide fishers with an opportunity to document what they are seeing and feed into the science of quota setting. In the Netherlands, smart cameras have been taught to differentiate between different fish species. With ongoing developments in technology, we envisage a day where scientific data will be accessed by fisheries, managers and fishers alike, in real-time, after each haul.

REM has been tried and tested for more than 20 years and is in use across many fisheries globally. In Denmark, following successful trials, REM is being rolled out across their fishing fleet which is very similar to that of the UK. Across the food sector, it has become standard practice to safeguard work places through the use of cameras. Cameras are mandatory in slaughterhouses in the UK, with recordings processed in line with data protection requirements to address privacy issues. Fisheries should be no different.

UK governments must seize the opportunity

Following Britain’s departure from the EU, UK governments are developing new ‘catching’ policies which if done right, could both improve the health of our seas and make livelihoods more secure.

Accountability and confidence will be central principles of these new policies, however, without equipping vessels with the tools they need to provide the required levels of at-sea monitoring these policies will fall short of their objectives.

Last month, one of the UK Government’s own statutory bodies, Natural England, released a report with the key message that Remote Electronic Monitoring (REM) with cameras is vital to achieving Good Environmental Status (GES) and recommended the immediate roll-out of this technology to the ‘highest risk’ fleets such as demersal trawls to: 1) help promote compliance; 2) collect data for data-poor fisheries; 3) protect sensitive species; and 4) contribute to achieving GES.

It was disappointing that UK governments did not take the opportunity to commit to rolling out REM across the UK fishing fleet when they produced the draft Joint Fisheries Statement – a document that sets out how fisheries will be managed across the UK now that we have left the EU.

There is still an opportunity, however, as the final version of the JFS has yet to make an appearance. We believe there is still an opportunity for all four government administrations to provide a unified voice in support of REM with cameras being a key element of fishing in UK waters. UK governments are still to develop their individual plans or ‘catching policies’ which should require REM as a key means of helping delivery and providing support.

The Scottish Government is to be credited for taking forward REM with consultations for roll-out to the scallop dredge and pelagic fleets, however, the concern is that plans to roll-out REM are not prioritising the vessels which need it the most.

© Alexander Mustard / WWF-UK

We know that gillnets and longlines carry some of the highest risk of seabird bycatch while whales are often accidentally killed in creel lines and other cetaceans like porpoises become entangled in gillnets and dolphins are caught in trawl nets. We are yet to achieve good environmental status for whales and dolphins, and the situation for seabirds is getting worse instead of better1 We also know that demersal trawls have the highest risk of shark and skate bycatch and discarding. REM can help to monitor bycatch rates and the use of mitigation measures.

Whatever changes are implemented in the new catching policies, we believe that the degree to which they are underpinned by robust at-sea monitoring with cameras will be a defining factor in achieving sustainable fisheries in the UK.

The question is… when will the UK governments step up and roll-out REM to the fleets that highest-risk fleets and embrace the benefits that REM brings for wildlife, fishers and the consumer?